By Madeleine Johnson | Valley News | Published 11/7/2020 | Modified: 11/8/2020

Until it was rechristened Veterans Day in 1954, Nov. 11 commemorated the armistice that silenced World War I’s guns at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918.

In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson declared that the anniversary of the armistice be observed with prayer and an interruption of work at 11 a.m., and in 1926, Armistice Day became an official federal holiday.

Its name has changed, and other conflicts have overshadowed the “Great War,” but Armistice Day remains part of Upper Valley life. Reminders of the 9,338 Vermont and 14,374 New Hampshire men who served in World War I are all around us. Some of them illuminate lesser-known aspects of America’s involvement in the “war to end all wars.”

Small neighborhood honors war’s giants

In a patch of green between Interstate 89, Route 120 and Heater Road in Lebanon, tucked behind The Fort and an auto dealership, is a tiny neighborhood of 1920s bungalows. Its street names honor the war’s leaders, from the supreme to the local: Marshal Ferdinand Foch, a French general who led the Allied British, French and American forces, Gen. John G. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, and Maj. Gen. C.R. Edwards, who led the U.S. Army’s 26th Division, in which most of the Upper Valley boys served.

The 26th, known as the Yankee division, was formed of 28,000 men from New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island regiments. Its veterans also referred to it as the “sacrifice division,” because only 15% of the original all-volunteer unit’s members survived the war.

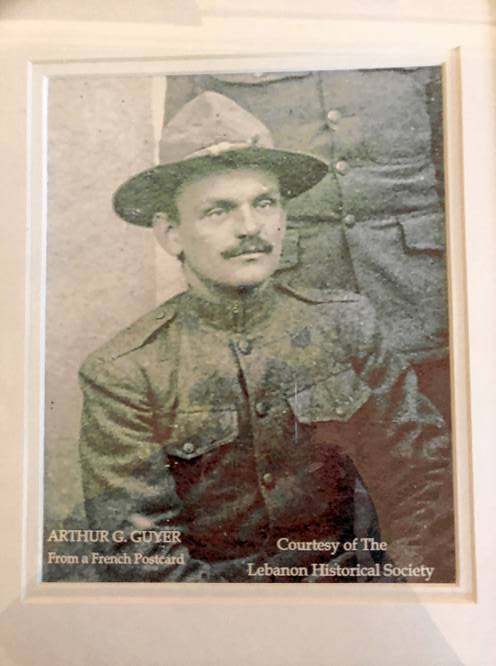

One of those who made the sacrifice was Arthur G. Guyer, whose name should be familiar to those who travel along Lebanon’s Mechanic Street, where the Guyer-Carignan American Legion Post is located. (Richard L. (Pat) Carignan fought in World War II.)

Guyer was the first Lebanon man to lose his life in France. He died near Belleau Wood, site of the famous battle, on July 20 or 23, 1918, while caring for the dying brother of the Lebanon post’s first commandant.

The 2nd Division, including the U.S. Marines, got the laurels for stopping the Germans at Belleau Wood. Less known is that the 26th, which relieved the 2nd, drove the Germans from the village of Belleau before pushing them back for several more weeks. For French Gen. Jean Degoutte, the members of the 26th Division were the “saviors of Paris.”

Gen. Edwards, commander of the 26th, was so disturbed by the destruction of Belleau’s village church that he vowed it would be rebuilt. It was, with donations from the 26th’s veterans. It is now the division’s monument in France.

Lebanon is not alone in making a Great War connection with its street names. Off Highland Avenue in Hartford is a similar small neighborhood along a road called Victory Circle.

American Legion posts

The American Legion, whose posts are a staple of Upper Valley life, is a durable reminder of World War I. It was founded in 1919 in Paris by 20 American officers, led by Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., to improve morale among American troops waiting to go home, and to foster post-war support and fraternity.

The Legion expanded across the U.S. in the 1920s, often naming posts for local heroes, such as Arthur Guyer. Norwich’s post is named for Lyman F. Pell, who was in the 26th Division and died in France. Canaan’s Weld-Webster Post is named for Verne Weld, who died in France, and post founder Jack Welch. Welch returned to Canaan, but died in 1923, probably from the effects of poison gas.

When most people think of World War I, they think of the horrors of trench warfare. But by the time America entered the fight, it had become a fast-moving, dynamic war, which had horrors of its own. Even on the move, as the 26th Division was, there was plenty of mud and poison gas.

The Germans may have been in retreat, but they were no less lethal. In addition, as they fell back toward their border, the pursuing Americans had to fight uphill to root them from a series of fortified ridges where they held out.

The autumn of 1918 was especially cold and wet. There was also an influenza pandemic. More would die from sickness than combat.

Town monuments

In the 1920s, several Upper Valley towns honored their war veterans with monuments. Canaan has a granite cenotaph on the green, which now includes the names of those who served in more recent conflicts. Lebanon honored its men with a plaque in Colburn Park. Hanover’s plaque, originally placed on the green, is now in front of Town Hall. Hartford’s plaque stood outside Town Hall before falling into disrepair, eventually to be superseded by a granite monument. Plainfield has a town plaque, and in 2018, it added a highway marker singling out native son Harry Dickinson Thrasher.

Thrasher, who studied with sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, joined America’s first camouflage unit, which copied the French and British teams that were applying artists’ skills to combat the novel threat of aerial surveillance. During stateside training, Thrasher created a “dead horse” that could hide a sniper. In France, Thrasher’s unit discovered that camouflage nets, much like those in use today, were more effective. They were also more dangerous than tricks like the studio-built horse. Thrasher died in battle in August 1918.

The national debate over burials

America had been divided about going to war, and it was divided about how to handle its dead. The ultimate resting places of these local men illustrates the conflict.

Theodore Roosevelt, whose son Quentin was buried near the site of his plane’s crash in France, spoke for those who felt that “where the tree falls, there it should lie.” Others, like the “Bring Home the Soldier Dead League,” disagreed.

President Wilson brokered a compromise that gave families until 1923 to choose whether the government would bring their loved ones home, or if they would be cared for in perpetuity in France.

In 1923, the American Battle Monuments Commission was created to build monuments and military cemeteries in France for the 116,000 dead interred in makeshift battlefield graves. The mostly Black staff of the War Graves Registration Service had the grisly task of cataloguing and consolidating the remains into eight new cemeteries. The commission hired star architects and planners to design the cemeteries.

In the war that followed, German troops respected America’s World War I cemeteries, and American GIs delighted in photographing them again in U.S. hands. America’s overseas World War II cemeteries, such as the one in Normandy, were also built by the Battle Monuments Commission.

Guyer’s family chose to bring him home to Lebanon. In August 1921, after a trip via Antwerp and Hoboken, Guyer’s brother Eddie picked up the body. Arthur Guyer was buried in Lebanon’s Mount Calvary Cemetery.

Final resting place in France

The families of Canaan’s Verne Weld and Plainfield’s Harry Thrasher made a different choice. Both men were reinterred in American cemeteries near where they fell: Weld at St. Mihiel and Thrasher at Oise-Aisne (where he is considered a New Yorker).

Another World War I legacy was the awarding of a gold star to mothers who lost sons. The U.S. government paid for more than 6,000 “Gold Star mothers” to travel to France to visit their sons’ graves — remarkable journeys in an age when travel of any kind was rare.

In 1930, Nora Grace Weld and Eliza Thrasher sailed for three-week trips to France. The segregated groups of about 200 mothers toured Paris and battlefields still scarred with shell holes and barbed wire. They placed wreaths at the Arc de Triomphe for France’s unknown soldier and met French and American officials. Weld’s group spent two full days among the 4,000 graves at St. Mihiel, which she called a “beautiful spot.” It was sad, Weld wrote, but “we felt a satisfaction we had not known before going to the Cemetery.”

Not all the legacies of World War I are cemeteries, monuments and Legion posts.

After their return, America often spurned its returning soldiers, denying them jobs and the recognition they’d earned. During the Great Depression, World War I veterans were accused of lacking patriotism when they marched on Washington to claim a promised bonus. When the Second World War came, it was World War I veterans — and the American Legion — who spared the new generation of veterans a similar humiliation by working to get the GI Bill passed.

Today, how many people in the Upper Valley still benefit from the education and the homes that the GI Bill helped their parents and grandparents acquire?

Madeleine Johnson, of Enfield, is a freelance journalist who has studied the Marines in World War I for many years. In 2018, she delivered a paper at the Marine Corps History Division’s World War I Centennial Symposium titled The Art of War: Laurence Stallings.

Correction

The column has been updated to correct Richard L. (Pat) Carignan’s name.